Dr. Robert Dziak, NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, Ocean Acoustics Project

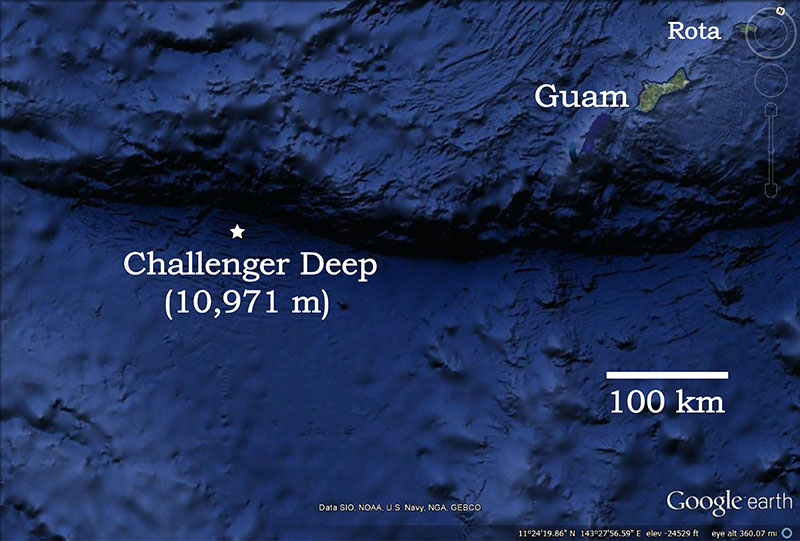

Challenger Deep trough in the Mariana Trench near Micronesia. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (1.8 MB).

In 2015, NOAA and partner scientists deployed a hydrophone to a depth of 10,971 meters (6.71 miles) within the Challenger Deep trough in the Mariana Trench near Micronesia. Using the hydrophone, researchers sought to establish a baseline recording the ambient sound levels at the deepest point in the global ocean in order to:

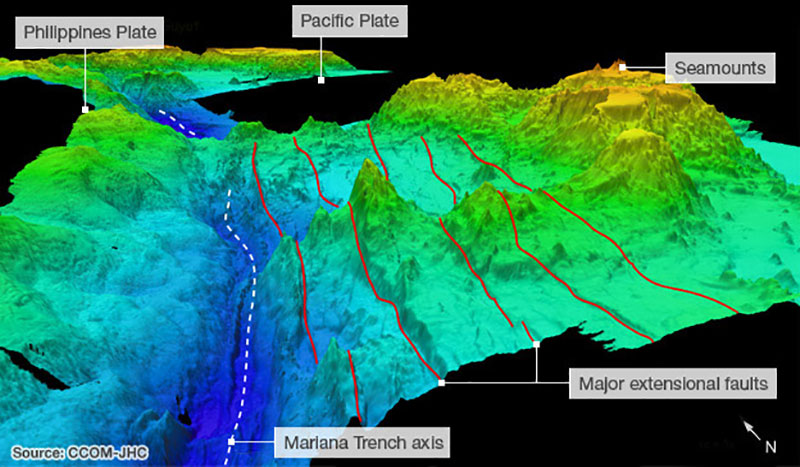

Three dimensional perspective of bathymetry at Challenger Deep, Mariana Trench. Challenger Deep is located along axis of Mariana Trench. Tectonic plates, major faults, and seamounts in the area are labeled. Image courtesy of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping - Joint Hydrographic Center. Download image (107 KB).

Engineers at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory built the one-of-a-kind deep ocean hydrophone to withstand the extreme hydrostatic pressures (more than 16,000 pounds per square inch, compared to the 14.7 PSI in the average home) at the ocean depths encountered at Challenger Deep. Because of the incredible atmospheric pressure at these depths, scientists had to drop the hydrophone mooring down through the water column at no more than five meters per second to be sure the hydrophone, which is made of ceramic, did not crack.

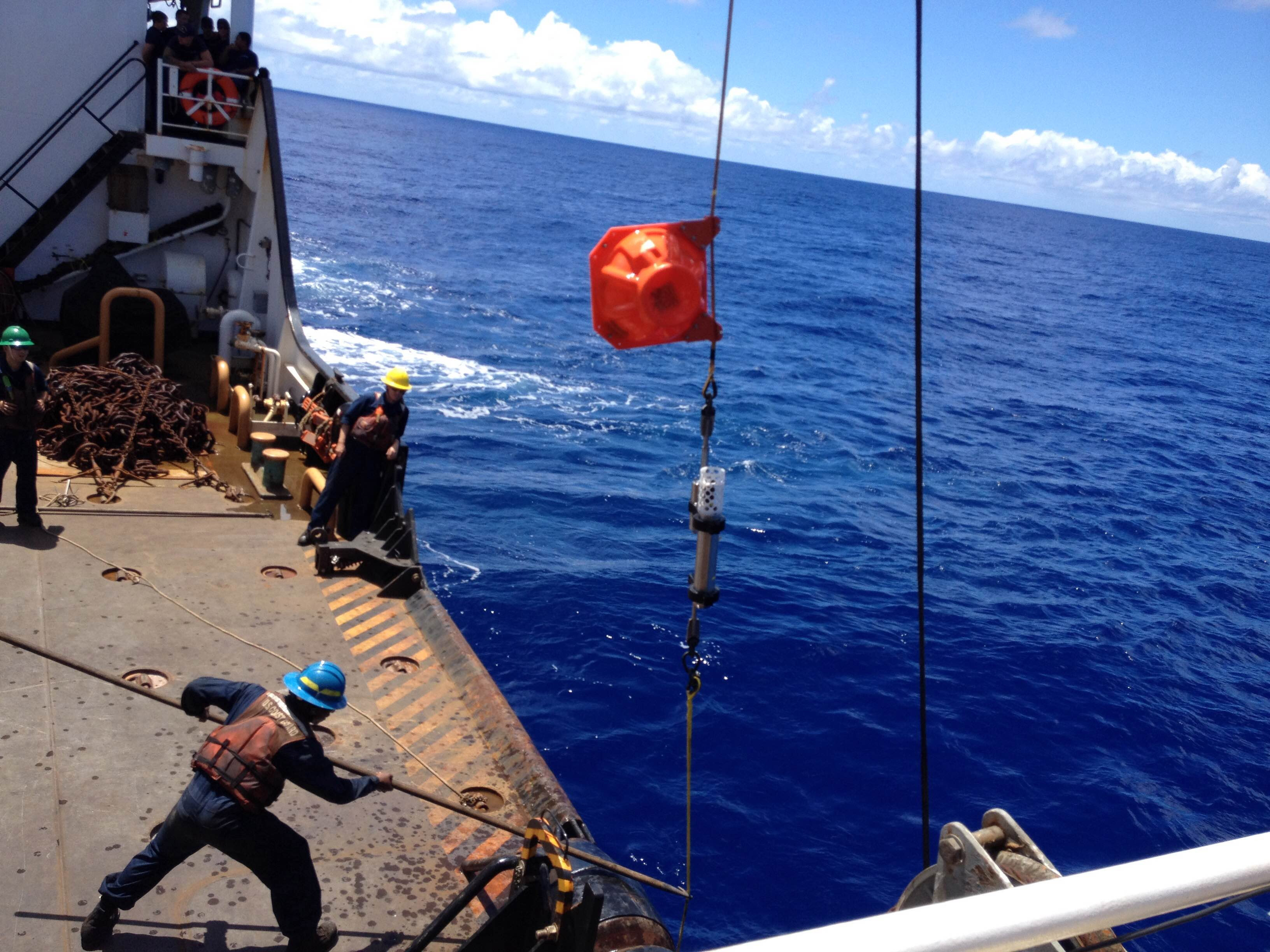

Petty Officer 2nd Class John Thompson, a boatswain's mate aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Sequoia, and Dr. Joseph Haxel, oceanographer with NOAA and Oregon State University, prepare special floats used to deploy a hydrophone in Challenger Deep near the Federated States of Micronesia, January 11, 2015. The crew of the Sequoia and NOAA scientists deployed the hydrophone in an attempt to listen to ambient sound in the deepest part of the Challenger Deep. Image courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard Petty Officer 2nd Class Tara Molle. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

Petty Officer 3rd Class Jonathan Gonzales, a boatswain's mate aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sequoia, homeported in Apra Harbor, Guam, prepares to throw a grappling hook to retrieve a NOAA hydrophone from Challenger Deep near the Federated States of Micronesia, November 3, 2015. Image courtesy of U.S. Coast Guard Petty Officer 3rd Class Dylan Hall. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

Researchers deployed the hydrophone from the Guam-based U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sequoia in July 2015. The device recorded deep-ocean ambient sound levels in the 10–32,000 Hz range continuously over 23 days. However, scientists had to wait until November to retrieve the hydrophone due to ship schedules and persistent typhoons. The device remained anchored to the seafloor until scientists returned.

Once they had a listen, researchers from NOAA, Oregon State University, and the U.S. Coast Guard were surprised by how much they heard.

Instead of being one of the quietest places on Earth, scientists found that at the deepest part of the ocean, there is almost constant noise. The ambient sound field is dominated by the sound of earthquakes, both near and far, as well as distinct moans of baleen whales and the clamor of a category 4 typhoon passing overhead. The hydrophone also picked up sound from ship propellers, as Challenger Deep is close to Guam, a regional hub for container shipping with China and the Philippines.

Deep-ocean hydrophone being brought back onboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sequoia after the deployment at Challenger Deep. The white top basket on top of pressure case protects hydrophone element Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (2.8 MB).

Human-created noise has increased steadily in recent decades. Establishing a baseline for ambient noise will allow scientists to determine if noise levels in the ocean are growing and how this might affect marine animals, such as whales, dolphins, and fish that use sound to communicate, navigate, and feed.

Example of a baleen whale call recorded at Challenger Deep. The call mostly closes resembles a Bryde’s whale call.

Examples of odontocete (toothed whale or dolphin) and baleen whale calls.

Sound of the propeller from a passing ship.

The sound of a magnitude 5 earthquake that occurred near Challenger Deep 16 July 2015.

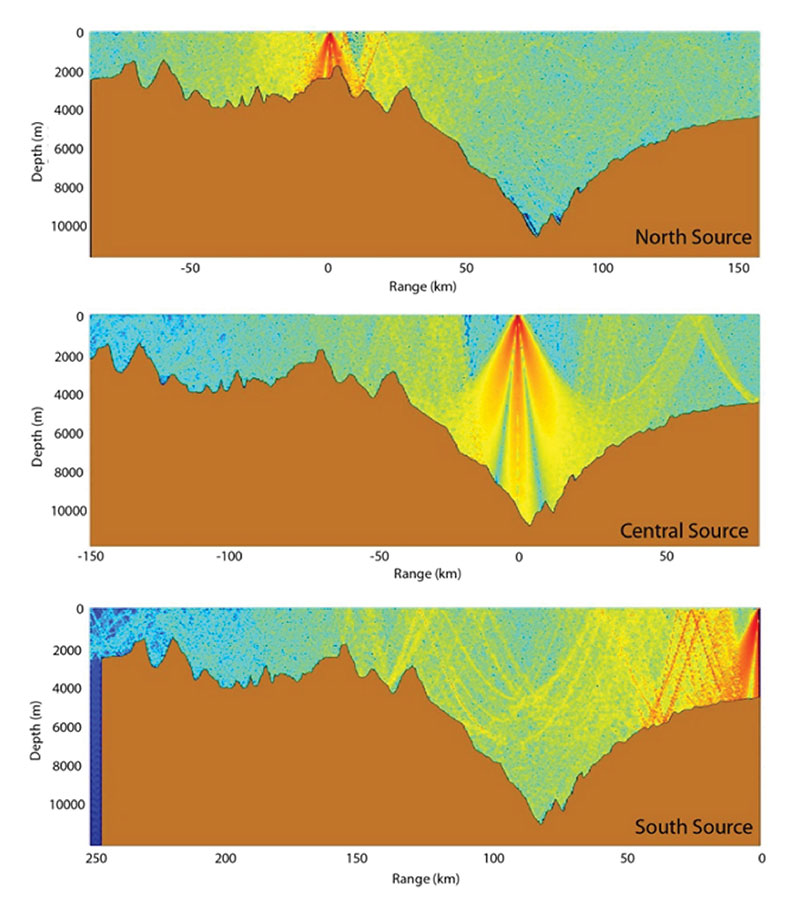

This chart shows three models of how sound should propagate from the ocean surface down the bottom of Challenger Deep. Image courtesy of NOAA. Download larger version (1.0 MB).